Where are $100B fintechs?

Almost all $100B finance companies are incumbents. Where are $100B fintechs?

It is a question I had in my mind for some time. Paypal is $65B, Adyen is $50B, Coinbase is $30B. What makes it hard for a fintech company to achieve the $100B outcome? Fintech achieved a lot and still holds a lot of promise, but it didn’t yet create a paradigm shift.

We all know paradigm shifts in tech - first with web, then with mobile, now it is happening with AI. These shifts give birth to generational companies - Apple and Microsoft, Amazon and Google, Meta and OpenAI. But finance by and large is still the same as 100 years ago. It had waves of innovation such as moving from regional to global banking and from offline to online - but these rather than complete shifts were just enablers of more jobs. Crypto is a promise, but we are a long way from it disrupting finance.

Why didn’t we have paradigm shifts in finance? I can think of three reasons - customer inertia, heavy regulation, but the most important although overlooked reason is that finance is a rigid and complex system. You can’t replace a part of it without interlinking with the existing web of processes. Anything that new fintechs build reinforces the same structure that was constructed by incumbents over hundreds of years. That’s why incumbents are structurally ‘moated’ against any fintech disruption. They are the largest companies by number of customers, by revenues and profits, and by market cap. But the most successful ones aren’t just sitting on their laurels - they keep adapting. This is what fintech companies can learn from them.

Will we ever see $100B fintechs? I definitely think so, but my guess is that they will be in payments, not in banking or asset management. Payments segment spurred by web and mobile, is newer and is still growing. It still has space for more players - biggest incumbents and biggest fintechs are in payments.

However, as I write below it isn’t just about growth, adaptability is more important to longevity, so whoever keeps adapting, wins. At the end of the day - the size of your company is a function of how fast and how long your ideas can keep accruing to your company, rather than to the market.

Biggest finance companies today are incumbents

Look through the list of largest finance companies in the world - all of them are traditional finance companies. The only fintech-ish company that has a market cap of over $100B today is Shopify.

The biggest companies are incumbents. Now let’s look at the progression of their market cap over time.

Notice how Visa, MC and JPM are dancing their own dance - remarkably they are traded higher than during covid peak, a feat that none of the fintechs have achieved yet. But the fall from grace of once mighty Citi and Wells Fargo - who are much smaller today than what they used to be, shows that value accretion isn’t a given for incumbents. What about fintechs? Have they accrued comparable amounts of value?

To compare value accretion between startups and incumbents I will use a ratio of market cap over age of the company. Dividing the current market cap by years since founding gives a common basis of value creation per year (not useful beyond illustration).

Visa and Mastercard are absolute beasts - on average they’ve been showing between $8B-$10B of market cap every year - this is the size of a good fintech like Sofi or Affirm. But taking out outliers, incumbents have about $2-$3B per year for an average of 150 years! Fintechs might grow faster, but their average age is at least 10x lower. Take Affirm and Amex - both have about the same number of $1B/year but Affirm is 10 years and Amex is 170 years.

This little exercise illustrates how enduring incumbents are. Even the ones that have seen their value diminished over time, are still orders of magnitude larger than fintechs.

Paradigm shifts in finance or why the biggest companies are incumbents

Why JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, Citi of this world are the most valuable companies? Traditional banks are largest finance companies outside of the US too - in the UK it is HSBC, in China it is ICBC, in Europe it is UBS. Why do incumbents have such a strong hold?

We haven’t had a paradigm shift in finance, in the same way we had in tech (also in pharma, in energy, in space). Fundamentally the way we manage our money hasn't changed. Paradigm shifts happen when old ways give in to new ways. Not just by simply making the old ways incrementally better, but when the new thing is 100x better than the old thing, making the old thing if not completely redundant, but at least somewhat obsolete. Cars and horses.

Obsolete doesn’t mean extinct. It could just mean that it isn’t at the center of the industry anymore. Benedict Evans writes that IBM was disrupted because mainframes stopped being the center of tech, as the Microsoft-led PC wave swept the momentum. Then PCs stopped being the center of tech giving place to mobile which helped propel Apple to dominance. Now it is AI’s turn.

What about finance? There were improvements that allowed for new jobs - like automation, globalisation or online payments. They were important - we can do things online, we don’t need cash that much, money moves faster than it used to, more people have access to finance. But the center and relevance of the finance industry hasn’t moved away from mainstream banking - people and businesses need bank accounts to get paid, to pay, to save and to borrow, same as 100 years ago.

Why we haven’t had paradigm shifts in finance? Here are my reasons:

Customer inertia is strong. People are conservative and utilitarian with their money - its not about vibes and emotions, it is about trust and reliability. Even when the new product is orders of magnitude better - cheaper, faster or just nicer to use - people still need convincing. Trust in traditional banks is still stronger.

Finance is regulation and capital heavy industry. Regulation is constructed around implicit support of biggest companies at the same time as it protects consumers. With fintech becoming mainstream, regulator’s tolerance for startup scrappiness is definitely decreasing. Unlike tech, finance regulation has borders - each new country, new currency or product requires their own licensing, compliance and capital. The last part is key - finance startup is a capital intensive endeavour, and incumbents already have scale that can absorb capital requirements.

All fintech reinforces the current system. Finance is a very complex and rigid system with a lot of interlinked parts. In a complex system you can’t just change one part and expect everyone to adopt it. Change is expensive, slow and switching costs are high. If the change isn’t embedded with the current linkage, it’s not going to work. And that’s why any new fintech is basically reinforcing the same system, rather than replacing it.

Of course then paradigm shifts are hard when there are constraints from all fronts - from customers, regulators and the system. Incumbents have moats that have nothing to do with what they build individually. These moats help them deepen their lead and compound their value.

Fintech companies have advantages in new ideas, fast execution and talent that could be used as moats, but unlike the above moats, these are relatively fast to erode. It is just a matter of time before incumbents adopt the same idea or the same product. This is good for customers, but not good for an individual company because their efforts are accruing to others in the market. The way incumbents such as JP Morgan, Visa and MC have been growing is precisely because they showed that they adapt faster than new threats emerge.

That’s why despite all funding and exits, fintech is still tiny - the global financial services market is $28T, while fintech market is $250B - or less than 1%.

Growth or longevity?

Company value is a function of cash flows and time - how much money a company could generate over its future of lifetime. Growing to $100B is very very very very rare1. But what do these companies do? Obviously a sure way to get to $100B is to have a long lifetime during which to generate lots of cash flow. But there are lots more ways to remain small:

short life + lots of cash: recent explosions in crypto companies that grew very fast but weren’t sustainable

long life + just enough cash: centuries old small businesses like English pubs or Japanese soy companies

short life + no cash: unfortunately there is a place where 99% of companies fall into

High cashflows means growing new businesses, expanding abroad, going wide and deep to claim a higher share. Long lifetime, on the other hand, is about adapting to threats and protecting what you have - dig the moats. Some companies are better at one, but you need both: growing is nice, but adapting and protecting that growth is as important.

Growth can be of two types - external or market growth, and internal or company growth (at the expense of competitors). It is easier to grow under the first type. As the company positions itself as part of the new segment, investor sentiment is super positive, even if the company isn’t dominating yet. But when the segment matures, there is inevitably only one growth lever - winning someone else’s business. And this is a hard game because instead of having a place under the sun for all, your company needs to go face to face with incumbents who have scale, distribution, trust and capital.

It definitely helps to start in the growing market. But adapting is necessary to continue with the growth loop. Although finance is a stable industry that hasn’t been ‘disrupted’, underneath the surface there is constant movement - new entrants, new regulation, new technology, new customer behaviour. Companies that adapt faster, have an upper hand in surviving. We talked about moats above, but you need the adaptability muscle precisely because internal moats don’t last. Various Top-100 lists looks different today than they did 10, 20 or 30 years ago. Also where are the companies covered in various books like Good to Great or Build to Last? If you’re not adapting to changes, you’ll fall behind very quickly. If you thought of a smart way to do loan decisioning, or cross border payments, or nice UI - incumbents can adopt that very quickly. That’s great for a customer, but the value of that feature you invented isn’t accruing to you anymore.

That’s why even though payment fintech are the largest, they reached their sizes after transforming from single product single feature to multi-suite multi-product companies to continue capturing the value they created. That’s why Stripe added more features to payments, Shopify moved from website window to a shopping platform, Klarna is building a payment network starting as BNPL. Even incumbents Visa and Mastercard grew so big because they adapted from being just bridges between different banks to supporting online economy.

In general fintechs as all startups excel at growth phase, but adaptation is something that incumbents mastered.

Who will be the first $100B fintech?

Payments is a growing segment. This explains the relatively large size of payment fintechs such as Shopify, Adyen, Stripe. On the other hand, more mature banking and asset management segments have been harder for startups to break into - instead of just riding the growth wave, you need to win in a contact fight. These more saturated markets are dominated by few competitors that don’t share space with startups - banking startups such as Affirm and Sofi are 10x smaller than incumbents. In asset management Coinbase and Robinhood took up the niches, but the prize is in the corporate asset management which is firmly in the hands of 5x larger incumbents.

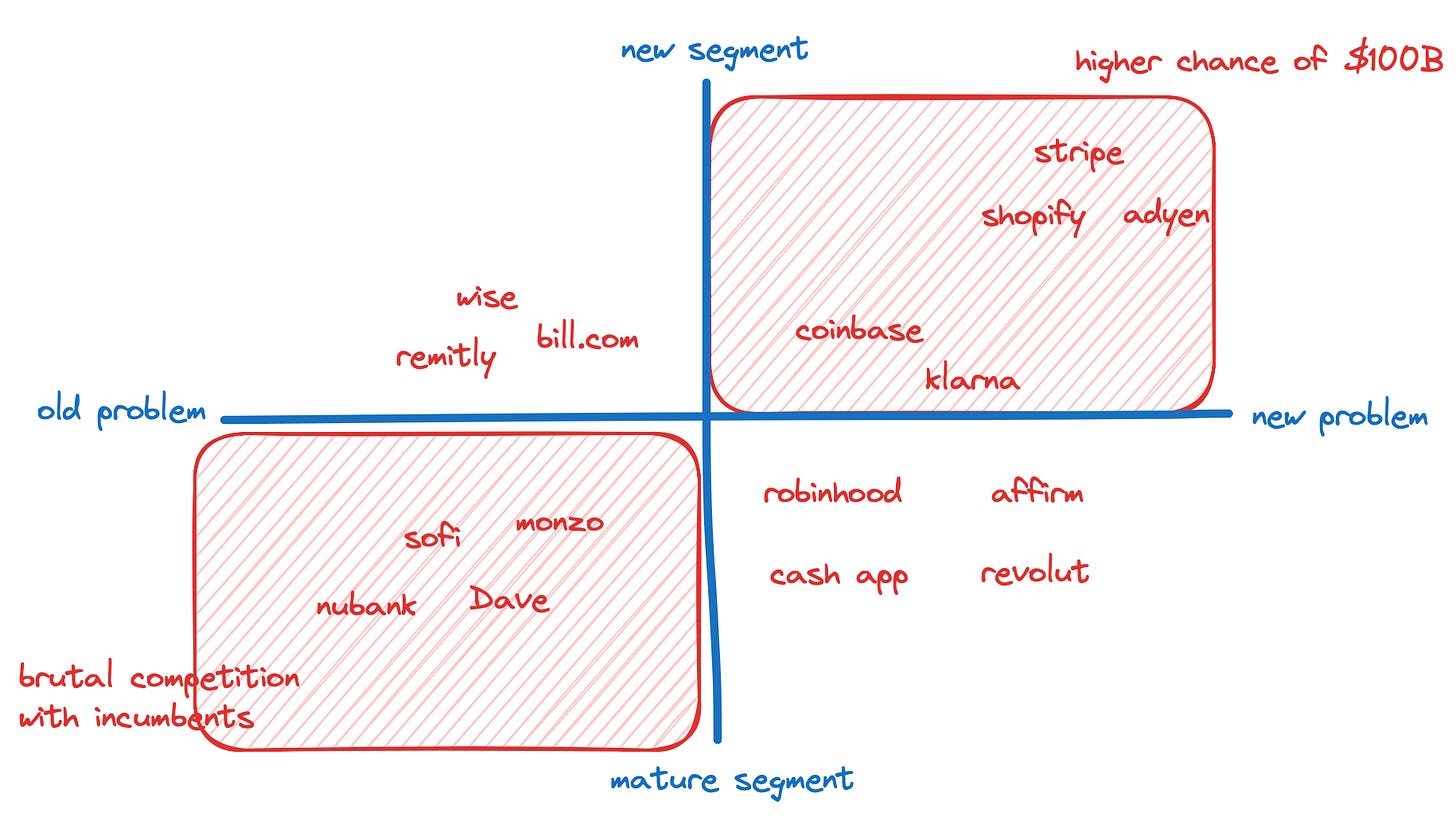

Working on a new problem in a new market does increase the odds of growing really big. This space has the highest value fintechs today. The hardest path is diagonally opposite - going after an old problem in a mature market. It is amazing and very inspiring to see founders tackle something that’s broken. But unfortunately because of the structural moats I described above and remarkable adaptability of incumbents in these segments, I think it’s going to be really hard for fintechs in this space to become truly big on their own.

That’s why big payment companies of today will grow to be the first lasting $100B fintechs. Maybe they haven’t paradigm shifted finance yet, but the scale, growth and market size is so big and they are so early, that it is inevitable they will grow into it if they continue adapting. This brings me the OG fintech Paypal. It had the best shot of becoming a lasting generational fintech company, but missed it. They almost made the paradigm shift happen - how revolutionary it was when you could just email money. Why Paypal fumbled?

Here is the last piece of a puzzle. You can’t become a $100B company if you don’t have a great leader. That’s what differentiates Citi and JP Morgan, or Paypal and Shopify. We had plenty of recent examples proving this - Satya with Microsoft, Zuck with Meta, Dara most recently with Uber. Leadership matters because the environment changes constantly - new competition, new regulation, your moats get obsolete. Markets as a collection of all companies go through natural pruning when losers lose and winners win. But it is incredibly hard to go through this pruning inside one company. Great leaders instill focus, speed, execution, and most importantly bravery.

I don’t think Paypal had a great leadership - they collected a vast array of jobs and services, customers and use-cases, losing their path to their true aspiration. I mention how Stripe, Shopify, Adyen have become big by adapting. But there is a difference between spreading your bets in pursuit of one aspiration, and collecting various businesses under one roof. I think Paypal is the latter. But it is still a $65B company - no mean feat. I just can’t shake the feeling that they lost the window of opportunity.

So if I were to end with some takeaways to startups they would be these:

chose a growing or new market, or better invent one

constantly adapt to new information, but keep your focus

have a great leader

Simple :) Shouldn’t have taken me to write a whole post to get here.

Thanks to Bruno Werneck de Almeida and Akash Bajwa for reading drafts of this.

Helpful reading:

Ben Evan on how to lose a monopoly by becoming irrelevant here

Julian Lehr on defaults being the biggest moats (he writes about hardware but it is very similar to finance - where defaults are everywhere) here

Jared Franklin on calibrating to new era in fintech (fintech is cool but hard work, lots of parallels) here

Jerry Neumann writes on taxonomy of moats and mentioned system rigidity as the biggest moat - this is especially relevant for finance here

Rohit Krishnan on company lifetime value as a concept that’s different from DCF here

Erik Beinhocker’s excellent book The Origins of Wealth, where he writes that complex systems require adaptability (among lots of other cool stuff)

There are about 32 million US registered businesses, and about 80 companies in the S&P500 that have a market cap of over $100B.

Great read. Thanks for writing this.

Correction to last point in "Helpful reading" section.

The book Origins of Value is edited by William N. Goetzmann and K. Geert Rouwenhorst (https://www.amazon.com/Origins-Value-Financial-Innovations-Created/dp/0195175719)

Erik Beinhoffer wrote Origin of Wealth (https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/22456)

Welcome back!